RIO DE JANEIRO, May 7 (IPS) - One young indigenous person commits suicide every 10 days on average in the centre-west Brazilian state of Mato Grosso do Sul. Blamed on the lack of land and opportunities, the proportions of this tragedy have drawn the attention of local and foreign experts.

The last young man to hang himself - the most common method of suicide - was a 20-year-old worker at a sugar mill, an occupation that is culturally alien to the local communities, but has become frequent among young people of the Guaraní-Kaiowá ethnic group because of the lack of traditional means of survival.

About 70,000 indigenous people, most of them Guaraní-Kaiowá, live in Mato Grosso do Sul - the highest concentration in Brazil after the northwestern state of Amazonas.

"Unless immediate measures are taken, there will be a new 21st century genocide of indigenous people," warns a report by the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI), an agency of the Brazilian Catholic Church.

CIMI’s annual report on "Violence against indigenous peoples", released on Wednesday, says that six indigenous people have committed suicide in Mato Grosso do Sul so far this year, while 40 have taken their own lives since January 2008.

The study points out that 100 percent of the suicides and 70 percent of the murders of indigenous people - of which there were 60 nationwide - took place in this state.

Most of the murders were the result of fights between the Guaraní-Kaiowá themselves, often within the same family.

"Added to the increased number of suicides, the picture that emerges is the self-destruction of this ethnic group, provoked by the precarious and violent reality they face," the report, coordinated by anthropologist Lucia Rangel, concludes.

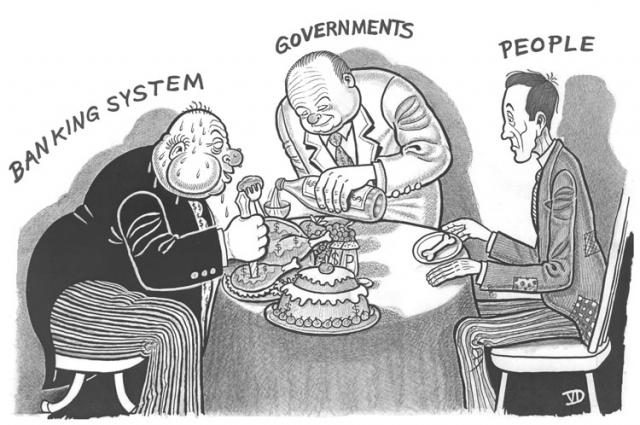

The vice-president of CIMI, Saulo Feitosa, told IPS that all forms of rural violence in Brazil, and particularly in Mato Grosso do Sul, are directly linked to the issue of land ownership.

The situation arises from "ongoing land disputes between indigenous people and encroachers, and the overcrowding of large numbers of indigenous people on small areas of land," he said.

"Many teenagers kill themselves because of their lack of options," said Feitosa, adding that the average age of suicides is between 13 and 17. There are various ways of explaining the suicides, but because of the age range, Feitosa's interpretation is that they are due to "trauma" related to the period in life when a sense of identity is emerging.

Feitosa said he thought young Guaraní suffer from accentuated conflict, "because their ethnic group is deeply religious" and "they lack their own places to pray, their forest with its foods for survival and their lands where their cultural identity can be reproduced, making their individual identity all the more fragile."

The village with the most suicides is Bororó, in the municipality of Dourados, 225 kilometres from the state capital, Campo Grande, where 13,000 indigenous people are crowded onto an area of approximately 3,500 hectares.

With land being so scarce, while they wait for the demarcation of a reservation, the indigenous people live in improvised shelters, many of them just canvas tents, hard up against each other, when customarily the houses of this ethnic group are far apart.

"They are forced to live in crowded conditions; the men go off to work in the sugarcane fields, where working conditions are often slave-like; the women stay home with the children, and this situation breeds alcoholism and violence, which leads to the alarming numbers of suicides and murders," said Feitosa, adding that the circumstances are exacerbated because different ethnic groups coexist here.

This process of "self-destruction" requires urgent political action from the government, according to CIMI, in order to correct the situation, demarcate land areas, reforest degraded zones and restructure living arrangements.

Feitosa said demarcation of communally owned indigenous lands has not been finally resolved in Mato Grosso do Sul, a fact he attributes to "heavy pressure from agribusiness" - agroexport companies that produce soybeans and sugarcane, mostly for processing into biofuels, as well as raising cattle.

Over the last 25 years, the village of Bororó has been hemmed in by big plantations. "The estate owners bought land and brought in cattle and soy and turned our land into monoculture plantations," Amilton Lopes, a local indigenous leader, told IPS.

"Now we have nowhere to live, to gather native medicines, or to find food for our children, and there are no houses for us," said Lopes, who attributes the violence to the inability to meet these basic needs.

Another negative factor is that toxic agrochemicals are used in the aerial spraying of sugarcane and other crops in the nearby plantations, and also fall on the indigenous villages, affecting people's health.

CIMI says that the indigenous communities in Mato Grosso do Sul are claiming 112 areas of their ancestral territories for themselves. Most of these claims are tied up in red tape.

Lopes' explanation for the suicides among indigenous people, which he links to the lack of land and opportunities to make a living, has an extra twist: family disintegration and alcoholism.

"The young people tell me that they would rather die than have nothing to eat or live on, so to support their families, they go off to work at the sugar mills and plantations. But the women are left alone with their children, and they often pal up with another man who can support them and feed their children. Then when the husband returns, he finds his wife with someone else. That contributes to the violence," he said.

These are outcomes of a "modern" society, which the indigenous leader contrasted with "traditional indigenous marriage," as he also contrasted the new patterns of food supply.

In the old days, the "fruits of the forest" and "honey from wild bees" provided enough food, but now they no longer exist as a food source, Lopes said.

Instead, there are the "supermarkets in the big cities, but we cannot afford to buy food there. But how we would like to eat those things!" said the indigenous leader, in whose view this contradiction of consumerism is even worse for an indigenous teenager who has no idea how he is going to survive in the future.

He ruled out an ancestral cultural motive for committing suicide, like the one prompting suicide among elderly people in other indigenous cultures.

"I asked the 'gran pajé' (elderly wise man) if there had been suicides and hangings in the past. He said, No, in the old days everyone lived in freedom as they pleased, and not in a pigsty as we live now," Lopes said. (END/2009)

Photo: smh.com

http://www.ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=46756

Related:

![Géopolitique : Union transatlantique, la grande menace, par Alain De Benoist [tribune libre] Géopolitique : Union transatlantique, la grande menace, par Alain De Benoist [tribune libre]](http://www.breizh-info.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/tafta.jpg)